Photo by J. Weinstein (GN91719_514Bd)

We’ve worked hard on the updating the Hall of Birds. Below are 10 reasons why you should come see the exhibit more than just once.

1. Doing projects like this reminds you of all the work that goes into an exhibit. In this case, the exhibits staff has been busy on all aspects of getting the walls repainted, the cases refinished, the glass cleaned, the mounts spruced up, the graphics redone, the text corrected, and new digital and visual aspects created. The result is beautiful and just for that; it is worth a visit.

George Chavez (left) and Joseph Mandrell, Tim Wallace, and Chris Montgomery from the Exhibits Department opened all the cases and cleaned the birds (Photo J. Weinstein).

2. This collection is truly one of the best such displays of avian diversity in the world. There are over 1000 mounted specimens on display of over 900 species. That means that each specimen was collected and then prepared as a taxidermy mount.

3. Marvel at the great taxidermy. Almost all date to the 1920’s and 1930’s although a number were collected and prepared for the 1893 World’s Fair and a few are new. The primary taxidermists included Leon Walters, John Mayer, Ashley Hine, Leon Walters, and Leon Pray. Pray and Walters were teachers and innovators, coming up with new and creative ways (like using cellulose acetate to recreate legs and other bare parts of larger specimens). Following in the footsteps of Carl Akeley, they worked not only with birds, but also were responsible for many of the mammals and fish mounts that are still on display throughout the museum.

Taxidermist Ashley Hine in 1925 preparing specimen mounts that are still on display today. On the left is a Common Black Hawk (Buteogallus anthracinus) and in the center is a Gyrfalcon (Falco rusticollis), both birds are in the Birds of the World section of the Bird Hall today (FMNH photo CSZ49969).

The Common Black Hawk in the Birds of the World section today (photos J. Bates).

4. Marvel at what it took to assemble this exhibit. A look at those specimens listed as mounts in the Bird Collection database reveals some impressive statistics about the birds mounts we have, not all of which are on display because there is not room in the current hall, or they are no longer in the kind of shape that warrants display, but they remain valuable scientific specimens.

Avian diversity is spread throughout the world, so in order to represent over 900 species with specimens; collectors spanned the globe. Our mounts come from 68 different countries and these are just the ones we know about for sure. For a percentage of our early mounts, locality data was not recorded (In the late 1800’s, specimens sometimes were purchased from biological supply companies that did not encourage locality data be collected by their collectors). For North American birds, we have mounts from 33 states and 7 Canadian provinces. Think about the amount of time and effort it took for different people to reach all these places and then skillfully collect specimens so that they could be displayed in this exhibit.

5. Enjoy the atmospheric projections. As I watched the development of this project all I could do was smile. As a kid, I can remember quizzing myself on the silhouettes of common birds that were featured on the inside covers of Peterson Field Guides. How far we have come? these projections help bring movement to the exhibit in a wonderful way. Thanks to the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology for vocal recordings and imagery that used to create the projections.

Atmospheric projection (Photo. J. Weinstein).

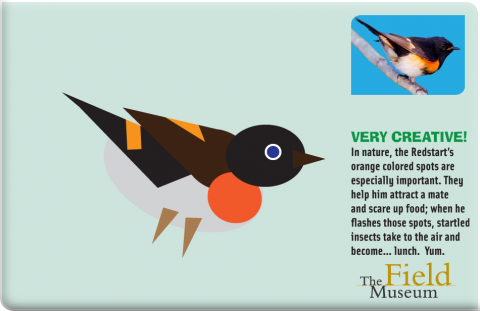

6. Play with and learn from the new ipad interactives. The creation of these interactives was the result of a great collaboration between the bird division and the exhibit department. This is an experiment for the museum and we expect it will have its fits and starts. But we are excited about what is accessible now, the creative “build a bird” interactives, the maps and the videos. And we are excited about the freedom it should provide us to update and augment information more easily in the future. The digital age opens doors for this traditional exhibition

.

The results of from the Build-a-bird interactive on an ipad in the exhibit.

7. Experience the Passion for Birds video. This video was created by the Liz Sung and Matrin Baumgaertner of Angle Park and they did an outstanding job. The video shows a broad diversity of people discussing what they love about birding. From young to old, professional to recreational, this video illustrates why birding is such a great entry point into the wonders of biological diversity. I am grateful to all of the great folks who were wiling to to interviewed for the project.

8. Check out the new science on the railings. Graphics designer David Quednau and his colleagues in Exhibits have done a wondrous job of making the railing throughout the exhibit as inspirational as the mounts. There is also new information about birds through out. Learn about how Shannon Hackett’s Avian Tree of Life study has altered how we think many groups of birds are related to one another. See what geolocators are and how they are providing new insight into the movements of smaller species of birds.

9. See the Artists’ Corner, which presents a spectacular selection of works by past masters from the collections housed in our library as well as modern work by the talented artists that are associated with the museum today. Different techniques and different points of view will inspire anyone about the interaction between birds and art.

10. People frequently ask what my favorite bird(s) in the exhibit are. I will usually try to get away saying I have a lot of favorites, which is true, but the Fawn-breasted Bowerbirds with a male’s amazing assembly of green objects laid out in front of his bower are on the top of the list. I have never been to northern Australia or New Guinea where these birds live. I don’t know for sure that I ever will, but seeing these birds and the bower always remind me of how great it would be to walk through a dry Eucalyptus forest and stumble across such an incredible sight.

I admit it, I’m biased, but I’m convinced that there is so much to see that you will want to come back and see this great exhibit again and again. And one more thing about the value of this renovation, most of these mounts have been on display for 80 to 100 years. If you conservatively calculate that 500,000 people per year pass through the Bird Halls, this means that these specimens have been viewed by at least 30 million people through the years. That is just up to the present, these mounts are so well done and have been maintained so well through the years (I challenge you to find the cracks that were recently repaired in one of the Ostrich’s legs by Dan Breems of the Exhibits team) that this number will just continue to rise with our improvements. Now remember that a majority of these visitors may never get to Arizona and Alaska much less Africa, Asia, South America or Australia and you realize that even in the age of television these displays offer incredible insight into birds of the world. Seeing a mounted Greater Roadrunner may spur someone to go to Arizona to see a live one when they had not considered it before. For those who are fortunate enough to have traveled, the exhibits offer opportunities to learn more about species they may or may not have seen from around the world. The inspiration these mounts have provided to those interested in birds in general or in ornithology is impossible to calculate, but to me, the birds of this world have and will continue to benefit from these collections which so many have worked so hard and so well through the years to bring to the public.

Gyrfalcon (Falco rusticollis, white phase) from the North American birds section (Photo, J. Weinstein).